Documenting Social Justice Protests #1: The Visual Impact of “Creative Cultural Resistance”

Tax Dodgers by Michael Fleshman from Flickr

Tax Dodgers by Michael Fleshman from Flickr

By Regina Austin

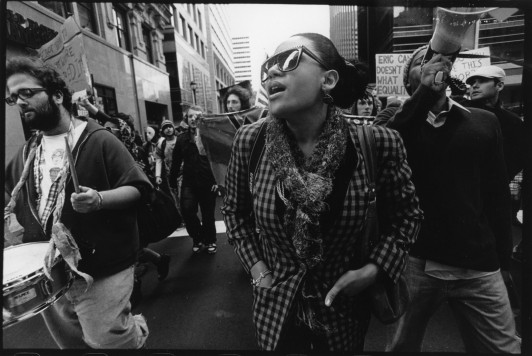

Direct action protest in the pursuit of social justice seems to be making a comeback. “Direct action” is loosely defined as the use of immediately effective acts, such as demonstrations or boycotts, aimed at an established authority or powerful institution, for the purpose of achieving a political, economic, or social end. According to activist trainer Daniel Hunter, citizens turn to direct action when they are locked out of official channels and institutions. Instead of presuming that power is amassed at the top and flows down to the people, direct action proceeds from the premise that that power flows upward by consent of the people. Among other things, direct action reduces the legitimacy and credibility of state actors by showing that they are undemocratic and unhelpful.

If protest assumes that power is based on people, it follows that the more people that are involved, the more power they have. Media is important for getting the word out and building a movement. “Creative cultural resistance,” a term activist trainer and puppeteer Nadine Bloch prefers to “arts of protest,” attracts media attention. With the proliferation of digital visual technology, the protesters can be the media and expand the impact of their activism beyond what was possible in the analog days of the 1960s and 1970s.

However, as the capture of documentary video footage and photographic images and their dissemination on social media have become an inevitable part of grassroots activism, uncertainties about their efficacy and ethics grow. Consider the questions raised by Sam Gregory, Program Director of WITNESS, in an essay in Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism: “[H]ow do we ensure that images generate more than compassion fatigue in viewers and contribute to meaningful action”? How can we “make sure that the footage that circulates helps facilitate voice, action and change rather than enabling apathy, or worse, social control, public humiliation, and state repression”?

Sam Gregory and Sensible Politics editor Meg McLagan challenge activist media makers who document protests to produce work that is authentic, “reaches its target audiences,” and “fits the needs of activists.” At the same time, the media makers should act ethically in creating, editing, and distributing their work, with due regard for the possibility that remixing and audience reception might undercut their intent to respect and protect those who confront injustice with direct action.

These concerns should not be foreign to public interest lawyers who are deeply engaged in struggles for social justice. Impact litigation and law reform efforts are bolstered by campaigns that carry a visual wallop, particularly through the use of social media. In some situations, taking up a camera, a cellphone, or an audio recorder in the context of a protest is an act of civil disobedience, a/k/a justified law breaking. Lawyers are called upon to protect the rights of activists and protestors both to use visual technology and media as protest tools and to resist their deployment by the state and private actors as instruments of repression and surveillance. It would surely not hurt for lawyers to know a little something about the arsenal of tactics protesters can use to advance their causes visually.

OccupyPhilly by Harvey Finkle

OccupyPhilly by Harvey Finkle

In October 2013, the Penn Program on Documentaries and the Law held a Visual Legal Advocacy Roundtable on the subject of “Preparing to Protest: Direct Action, the Arts of Protest and Media Impact.” Speakers included direct action trainers, activist media makers, communications scholars, and lawyers. In the audience were members of groups and organizations that employ direct action in their quest for law-related social change as well as public interest lawyers. The topics considered were: (1) proven techniques for maximizing the visual impact of social justice protests; (2) the obligation of activist media makers to produce work that is authentic and effective, while preserving the safety, privacy, anonymity, and autonomy of protesters; and (3) the concrete role lawyers play in assisting and protecting activists with regard to visual technology and media.

Video of the Roundtable presentations, edited by Adam Brody, is now available on the website of the Penn Program on Documentaries & the Law and on YouTube. The talks are liberally illustrated with images. The admonition “Show, Don’t Tell” is hardly a cliché when the subject is documenting social justice protests.

Roundtable Participation by Harvey Finkle

Roundtable Participation by Harvey Finkle

If you are interested in ideas for tactics that are more visually impactful than the marches or candlelight vigils that are so ubiquitous on the 11 o’clock news, I urge you to see and listen to Daniel Hunter on “Direct Action and Activism: Lessons Learned Through Casino Free Philadelphia,” Nadine Bloch on “Creative Cultural Resistance: Diverse Approaches to Art and Activism” and Che Gossett on his direct action hero Kiyoshi Kuromiya. During the lunch break, Roundtable participants made their own protest signs. You can see the results in a short video made by two former PhillyCam interns, Ian Abell and Nick Dagostino.

In a subsequent post, I will consider the contributions of several Roundtable speakers who address the strategic or tactical use of protest imagery in a world where material struggles are fought in part on a cultural terrain and the significance of social interactions to the effective and ethical use of visual technology in the context of political activism. In a concluding post, I will introduce the talks of three lawyers who facilitate or moderate the interaction between political activism and visual technology in very different ways. ![]()