Portraying Young Black Men “with a Background”: An Authenticating Audience Reviews “Evolution of a Criminal”

By Regina Austin

Many of those protesting officer-involved killings in Ferguson, Staten Island, Cleveland, and elsewhere strongly believe that the way in which young minority males are portrayed in the media impacts how they are treated by the police, prospective employers, and ordinary fellow citizens who encounter them on the street. Especial objection has been voiced about the way in which young minority male victims of state violence have been “shamed” by the authorities and the media for involvement in totally unrelated encounters with the criminal justice system.

Changing the narratives nonfiction media tell about young minority men with a (criminal) background may positively impact and prolong lives. It is important, then, to consider what is problematic about typical nonfiction media representations of such young men. How should they be portrayed?

Those were the issues on the table at a recent screening and discussion of Darius Clark Monroe’s “Evolution of a Criminal” recently held at Penn Law School, with a grant from the Netter Center for Community Partnerships. “Evolution” is an autobiographic account of Darius’s decision as a teenager to hold up a branch of Bank of America near his home in Houston with two of his friends and the consequences that followed. He was caught, pled guilty, and wound up being sentenced to five years in an adult facility. Fortunately, a juvenile offender program there provided him with educational opportunities (that are no longer available). He got his GED and started college while incarcerated. After his release, he completed college and was accepted into the prestigious film program at New York University. “Evolution” started as his student thesis project.

Director Darius Monroe participated in the post-screening discussion along with four other black men, between the ages of 21 and 45, each of whom had some direct familiarity with aspects of Darius’s life story. Hiram Rivera is the executive director of the Philadelphia Student Union which organizes students around educational issues; he has experience teaching video production to teenagers. Shawn (“Frogg”) Banks is a former drug dealer and the survivor of a violent kidnapping who is concerned about the impact of post-traumatic stress on young people; he is also involved in video and music production. Darren Brown is a participant in a workforce development and violence prevention program that focuses on environmental stewardship. The moderator was Michael Lee, a young lawyer who was a communications major in college; he now runs the Criminal Record Expungement Project which helps people clear their criminal records of old arrests and minor misdemeanor convictions.

The panelists comprised what I have called elsewhere in this blog “an authenticating audience,” that is, one that “speaks from genuine experience and draws on an engaged, organic or grounded expertise.” They paid particularly attention to the details of the documentary, gave it a close reading, and offered a critical reception. What follows is my take on their responses to “Evolution of a Criminal.” They appreciated the film because it demands a deeper journey into the lived reality of young black men with a background.

A Complex Portrait, Pitfalls, Systemic Traps, and State Violence Included. The panelists seemed to agree that “Evolution” as a portrait of a young black male with a (criminal) background was a departure from the norm. Young minority men are most often portrayed as either good or bad, with there being nothing in between. Even their redemption stories are presented as a movement from one extreme (bad) to the other (good). They are rarely depicted as complex three-dimensional subjects living in a three-dimensional world.

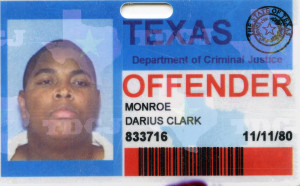

Darius’s self-portrait is different. He was a good student, “a scholastic achiever” as one audience member put it, not a street kid. He took AP Honors courses. But his family was struggling financially and had been set back even further by a home burglary. He was pushed to the edge by economic insecurity, a situation not uncommon among black families that cannot make ends meet with two parents working two jobs each. So Darius decided to rob a bank.  Darius Clark Monroe

Darius Clark Monroe

As Hiram asserted, the fact that Darius got into trouble with the law shows that structural forces that lead to criminal behavior can impact even minority youth who excel academically, if they are poor. They lack the vocabulary with which to analyze the institutions and systems that account for their precarious economic and social situations. (Why exactly was it okay for Bank of America to rob people of their homes through foreclosure and make billions, yet not be held accountable?) Young minority kids have “no clear vision of what out (freedom) looks like” or “what it takes to get out from under.” The media does not much help them to analyze their situations, escape the systems that entrap them, and find a way to make it to and pay for college.

That is not to say that young minority males should avoid taking personal responsibility for their behavior. Drawing on notions of restorative justice, Darius is shown in the documentary apologizing to the victims of his crime and asking for their forgiveness. Darius said that he hoped that his film shows that even “under the umbrella of oppression,” young people have an obligation to be “positive, push forward, motivate” themselves, and not quit just because they are being oppressed and marginalized. One must be responsible for crafting one’s own destiny.

Still, it is possible to criticize the kinds of expressions of contrition the public demands of minority ex-offenders. Hiram argued that Americans love apologies and acts of contrition. Black and Latino men are made to pay penance for their crimes and for who they are. They are made to offer regrets free of any acknowledgment of “the pitfalls, systemic traps, and state violence” that “set up brothers” in the situations in which they find themselves. America, on the other hand, while it likes expressions of remorse, apologizes for almost nothing it has done in the past to disenfranchised people, according to Darius.

Stories of Redemption That Deserve More Credit Than They Get. The general consensus seemed to be that Darius did not undergo a dramatic transformation in prison. He was pretty much the same law-abiding, studious person after his crime as he had been before it. Yet, though his post-prison life can be read as a “redemption” story, it did not automatically redound to his credit. Stacey Brownlee, the former assistant district attorney who prosecuted Darius, challenged the evidence suggesting that “he had turned his life around,” even although he had been out of prison for 10 years by the time he interviewed her. “I’m not going to tell you that I’m 100% convinced. You come back to me when you’re 50 years old and your criminal history is clean; I’ll be completely convinced. There’s always going to be the little prosecutor part of me that says I’m being scammed. Face it! If anybody is going to scam law enforcement or a prosecutor, … it’s going to be a smart, good looking kid with a good mind.” Yet, as a public defender in the audience asserted, she seemed to be taking some credit for Darius’s successful reentry into life after prison.

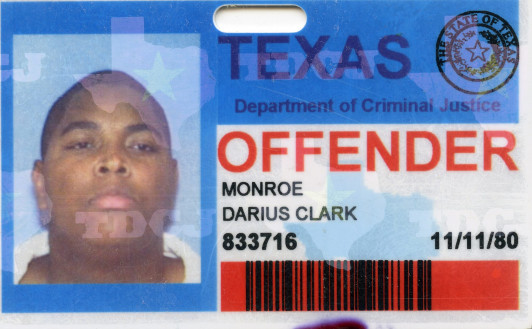

Darius suggested that the former DA was a complex figure. He thought that her point of view, though seemingly extreme, was one held by many others. Even one of his NYU professors admitted he probably would not have hired Darius as a graduate assistant had he known that Darius was a formerly incarcerated person. Darius gave the DA credit for “not sending me up the river for 99 years.” His very lenient sentence was “an anomaly.” Though he was devastated when it was handed down, he came to appreciate it after he got to prison and realized that he was surrounded by inmates serving terms of 50 to 99 years. It was also the DA who told him, as he was being led off to prison, “I know that your mother will have to do (serve) every single day with you.” Which is to say, “this is impacting everyone around you so I hope you’ve learned your lesson.” At the same time, he has come to understand that actors in the criminal justice system have very little respect for people’s time and lives. The prisoners do not get back the time they serve. A long sentence is a devaluation of another person’s life. Michael Lee & Shawn Banks

Michael Lee & Shawn Banks

Going Public about the Hardships of the Reentry Process. Moderator Mike Lee challenged Darius for his film’s silence about the course of his reentry (the transition from prison to parole or probation and on to freedom from oversight by the criminal justice system). “Evolution” does not explain how he got from prison to NYU. He’s talking about it now. What changed his mind about keeping his status as an ex-offender private?

Darius explained that, when he got out of prison, he wanted to “put that chapter of his life behind [him] and move forward.” He did not want to be stigmatized. He blocked his crime, the people involved, and his imprisonment out of his mind. He did not disclose his record on his application to NYU because he wanted to get into film school based on his transcript and skills and not who or what they thought he was. In any event, the application only asked if he had been convicted of a drug felony which he had not. At some point during his time at NYU, he realized that he had nothing to be ashamed about, especially if he was talking about the truth. He began to ask himself how did this kid get in trouble and wind up in the prison system. He began to question the systems that are rendered invisible because they are run by people. He became furious about being part of a community that has been constantly under attack.

Darius acknowledged the help he received from people who had been previously incarcerated. After numerous rejections, one of his first jobs was at a place that hired ex-felons. He got it through someone he had been in prison with. His aunt has a construction business and hired him despite his having a record. He had the support of individuals who were previously incarcerated, who did not stigmatize him, and who allowed him the opportunity to succeed and grow. Other people who are or have been incarcerated do not have that opportunity. They do not get second and third chances. They may be shot down in prison or are too embarrassed to ask for help.

A member of the audience suggested that in communities of color, family members do not talk about patterns of incarceration. Darius knew that his biological father had briefly gone to prison but not his Aunt Carlos or Uncle Cory who are interviewed in the film. He does not even now know what his uncle did. Life is hard and people are trying to get through the daily activity of surviving. Those conversations are needed. “It felt like therapy” when he turned the camera on and all kind of information was divulged. It might not have changed his mind had he known about his family’s history before he robbed the bank because his family’s finances felt extremely dire at the time. His conduct was not tied to that history, but to his immediate circumstances.

Exposing How the Danger Posed by Young Blacks Is Exaggerated. Mike Lee also asked Darius about the flyer that was pinned to his locker describing the bank robber as a black male in his early thirties. Darius had just turned 16. Darius replied that the over-aging of young black men reflects the exaggerated dangerousness ascribed to them and the existence of an “extreme empathy gap.” Viewing a teen as a grown man increases the odds of his being certified as an adult and sent to an adult prison. This happens to young black men and “angry” black women. They make juvenile choices, “the kind of mistakes that teens would make,” not adult or grown up choices. The over-aging prevents the larger society from seeing their humanity (a humanity includes the possibility of making good and bad choices) and prevents the expression of sympathy and regard for them. And as panelists Shawn and Hiram suggested, it makes the children more vulnerable to policing and denials of protection when they are in danger. Darren emphasized the way in which cultural practices maintained across generations inappropriately leads to misjudgments and suspicions about minority males that can only be lessened by their engagement in their communities.

Hiram Rivera & Darren Brown (center)

Hiram Rivera & Darren Brown (center)

Less than Exceptional, More than a Stereotype, Just About Average. Finally, a member of the audience asked Darius if he really represented the average young black man. The mere fact that he was attending high school and about to graduate suggests he was exceptional. So does his academic performance. Darius replied that he does not consider himself to have been an exceptional young black man. His household was average; his family was broke. He had an average upbringing.

The high school he attended was 98% black. The teachers were black. There were kids in his school who could not read and others who went to Harvard. He did not undergo a miracle transformation. He did not turn into someone new. He robbed a bank and then went on to do what he probably would have otherwise done. There was no bogeyman who took ahold of him. He had an interest in the arts throughout his entire life. He had time on his hands when he was incarcerated to write. In prison, he met a lot of guys who were “incredibly smart “and “really, really gifted.” They had “so many tools and gifts to give society.” They were robbed of that. He met more people like himself who got caught up in the struggle. Darius’s maintained that his story is “not some anomaly. It’s common.” It’s reflective of “an epidemic.”