“Abacus: Small Enough to Jail”: A Minority Bank, Racial Bias, and the Democratization of Credit

By Regina Austin

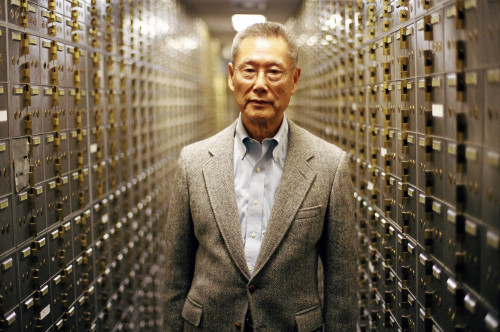

Abacus Federal Savings Bank is a small institution that is headquartered in Manhattan’s Chinatown and serves an Asian American and Asian immigrant population. It was founded by Thomas Sung, a Chinese American, in 1984. One of his daughters (Jill) is its president and CEO and another (Vera) is a director and its closing attorney. The bank was the only financial institution tried for mortgage fraud in the wake of the subprime lending debacle that led to the Great Recession of 2008.

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail, a documentary by Steve James, follows the course of the criminal proceedings from the perspective of the Sungs. The film offers three very important insights on economic equality and minority-group advancement. First, Abacus provides a window into the operation of a small family-run, community-focused ethnic bank, both in general and in a time of crisis. Second, Abacus exposes the incompetence of a prosecution that, in failing to understand the cultural context of an ethnic minority bank and its customers, winds up exploiting and reinforcing economic stereotypes and biases about them. Finally, Abacus illustrates the importance of informal and flexible lending practices to bringing the unbanked and underbanked members of racial and ethnic minorities into the formal market for financial services and credit, a notion known as “the democratization of credit.”

I.

In December of 2009, Vera Sung discovered that Ken Yu, one of Abacus Bank’s loan originators, was writing “liar loans,” i.e., loans supported by false documentation of such information as the borrower’s job titles, income, and sources of down payment. The bank immediately reported the matter to the appropriate bank regulators and hired a consultant to unearth the full extent of the fraud. Yu was also extorting money from borrowers. When one of them went to the police, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office got involved.

In May of 2012, District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. announced a 184-count indictment against the bank and 11 of its current and former employees that accused them of, among other things, conspiracy, grand larceny, falsifying business records, and residential mortgage fraud. The chief witness for the state was none other than Ken Yu. The prosecution asserted that knowledge of the practices of the bank’s corrupt loan personnel went high enough up its hierarchy to charge the bank itself with participating in “a systematic scheme to falsify and fabricate loan applications to Fannie Mae.”

Abacus the Documentary shows the great lengths to which the Manhattan DA’s office goes to make a tiny minority bank out to be a prime example of the abuses that led to the financial crisis. Abacus is America’s 2,651st largest bank. By contrast, gargantuan institutions like Citicorp, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo received millions in bail out funds, but were never prosecuted because they were “too big to fail.” Vance et al. seemed to think that Abacus and the big banks had much in common (“The principle was the same.”), but in truth, whatever the similarities in their loan underwriting and processing practices, Abacus did not deal in subprime mortgages and expected it borrowers to repay their loans which they did. Moreover, Vance et al. underestimated the resolve of the Sungs who refused to passively plead guilty to a felony and made the “courageous and expensive choice” of fighting the charges.

And so the investigation that began in 2010 led to a 4-month trial and 9 days of jury deliberations in 20I5. The case focused on 31 of the thousands of loans that Abacus sold to Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Association) which bundled them into securities which were then sold to investors. The verdict was a complete exoneration, a term the losing assistant D.A. refuses to use, but victory came with a price tag of $10 million in defense costs. If the criminal case was not an abuse of power, it clearly was a monumental waste of government resources devoted to “cleaning up” the loan department of a bank that was more than amenable to accepting greater regulatory and compliance oversight.

As Abacus the Documentary shows, the fierce defense the Sungs mount saves the bank and preserves Mr. Sung‘s good name, but leaves Mr. Sung worried about the lasting impact of the prosecution on the hardworking community the bank serves. Mr. Sung opened the bank to help Chinese immigrants obtain loans for homes and small businesses; he thought that it was unfair that people in the community deposited millions of dollars in mainstream banks, yet were refused loans. Abacus Bank, named after the Chinese calculator (“a national treasure”), provides a mechanism for bringing immigrants into the formal banking system. For Mr. Sung, the indictment of the bank “cast a shadow” on the entire community. He fears that the evidence presented over the course of the long trial suggests that “everyone the bank deals with is a liar” and that “Chinese people are not law abiding.”

Mr. Sung’s concerns seem warranted. Abacus Federal Savings is a Chinese American-owned financial institution located in a Chinese American enclave and serving immigrant customers from China. As such it is associated with a racial and ethnic minority whose ways of doing business are stereotyped by outsiders as closed, alien, dishonest, and corrupt. The prosecution and the trial could be read as both confirming that categorization and thereby negating the charge that the D.A.’s actions were the product of hostility or prejudice against a minority group. This possibility is reflected in a couple of the reviews of the documentary which both contend that the film leaves a reasonable doubt about the role racism or ethnocentrism played in the criminal proceedings and use language that may appeal to readers with latent biases.

Director Steve James highlights Thomas Sung’s positive identification with George Bailey, the Jimmy Stewart character in the Christmas classic “It’s a Wonderful Life” (which I have never been able to sit through). Comparing Abacus Federal Savings to Bailey’s Building and Loan, Stephen Dalton in the Hollywood Reporter asserts that Abacus is “not quite that kind of folksy family business.” He concludes, “Some accuse the DA’s office of racial bias, but the evidence does not really stand up. It appears more likely that the Sung family were singled out because they were an easy target rather than for their ethnic origins.”

Owen Gleiberman’s review in Variety notes that the Sungs “do not open up their inner lives to the camera.” He further concludes, “If the film is, in fact, about a real-life George Bailey, the forces arrayed against him remain hidden behind a curtain. We have to guess about the nuts and bolts that are driving the central scandal.” Gleiberman asks, “Were the fraudulent documents a smoking gun, or were they a form of benign corner-cutting related to how business was routinely done in Chinatown? From what we’re shown, it’s hard to say; the notion that the government had some reason to consider indicting Abacus doesn’t seem out of the question.”

This brings us to the heart of the matter. The crucial question is whether the documentary’s expanded cultural contextualization of Abacus’s mortgage lending operations is effective in countering or eroding anti-Asian American and anti-Asian immigrant preconceptions related to economics and financial transactions. That is a tall order, but I think the film meets the challenge. Indeed, what James has attempted in Abacus needs to be done for other minority groups laboring under clouds of cultural confusion blocking their access to democratized credit markets.

III.

Nothing in Abacus suggests that Abacus Federal Savings plays fast and loose with Fannie Mae’s money. Quite the contrary! Of the 3,000 loans it sold to Fannie Mae, only 9 defaulted. Abacus has a very low default rate. Moreover, none of the 31 questionable loans that were at issue in People v. Abacus was or is in default. The borrowers appear to have been qualified in fact. The bank did not achieve its stellar record by employing quick, easy, and potentially illegal shortcuts. Insofar as its underwriting practices were concerned, writer Jiayang Fan, who appears in the film, concluded in her New Yorker piece on the bank that “[Thomas] Sung developed the use of nontraditional borrower profiles – a way of examining routine household payments to assess creditworthiness among people who don’t have a typical credit history.”

Abacus Federal Savings capitalized on the advantages generally enjoyed by ethnic and/or immigrant minority-owned banks that serve customers from the same group. Such banks rely on cultural solidarity and a professed ethic or mission of community service to attract deposits and customers. The banks understand the cash economy in which their customers operate and the significance of cash flow as a form of collateral. They speak the customers’ languages. In determining creditworthiness, they rely on local, unconventional, unique, nonstandardized, and informal sources of information regarding spending patterns, employment patterns, and saving habits within the community; common values and norms, particularly regarding trustworthiness; and business and social networks in which reputations are developed and tested.

Of course, for Manhattan D.A. Vance, the lack of defaults and evidence of the borrowers’ actual creditworthiness were irrelevant; what mattered was the supposedly false documentation the bank supplied to Fannie Mae to support its loans. Yet, the prosecution was not always able to establish its claims that Abacus failed to honestly satisfy the formal requirements.

At various points in the proceedings, when prosecutors attempted to prove a document false, their ignorance of the culture of the people with whom the bank deals proved to be a stumbling block. Fannie Mae apparently forbids the use of loans as a source of money for a down payment. The state attempted to show that the bank allowed borrowers to submit fake evidence of “gifts” from parents and relatives that were really “loans” in disguise. The prosecution opened up a can of worms for itself when it turned out that there is no bright line between gifts and loans in Chinese culture. Any undergraduate who has taken an introductory sociology or anthropology course should know that the distinction between “a gift” and “a loan” depends on norms of reciprocity and exchange that vary across cultures.

The fluidity of these concepts should not have stumped the state’s lawyers. The line between “gifts” and “loans” is none too bright in cases where non-Asian American families are deciding how to help a young couple purchase of a home or start a business, for example. In figuring out whether to “style” the transaction a gift or a loan, the benefactors/lenders take into consideration the demands of the lender or mortgage guarantor or insurer, as well the implications of the tax laws.

In general, across a wide swath of the society, informally documented information and informal connections and relationships influence traditional formal home mortgage and small business lending. Social capital, the currency of informal communal networks, greases all kinds of financial transactions. The amount of economic and informational support borrowers can get from whomever they know makes a difference in their ability to acquire access to credit on the best possible terms. In addition to family ties and friendships, there is evidence that preferential group solidarity among the white majority is at least as potent as that uniting some racial and ethnic minorities when it comes to assisting group members to get ahead in the market for credit. Groups with little collective experience with or connections in formal credit markets suffer by comparison.

Abacus utilized the social and cultural capital of its customers to enhance their opportunities to reap the benefits of participation in formal markets for credit by accurately predicting their creditworthiness and supplying paperwork that was truthful or acceptable according to standards prevailing among responsible borrowers in the community. It is not clear that Fannie Mae did not realize that.

Abacus utilized the social and cultural capital of its customers to enhance their opportunities to reap the benefits of participation in formal markets for credit by accurately predicting their creditworthiness and supplying paperwork that was truthful or acceptable according to standards prevailing among responsible borrowers in the community. It is not clear that Fannie Mae did not realize that.

IV.

The bridge linking unbanked and underbanked marginalized groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, and persons of low socioeconomic status, with formal credit markets offering competitive and attractive terms begins with informality. It is necessary to start with people where they are and work with what you get.

In a previous paper, I describe the forms of informality that are associated with this sort of “democratization of credit” as follows:

“[I]nformality include[s] the embeddedness of the lender in the local community and in the social relationships that promote financial decisions which acknowledge the value of the reciprocity of respect and responsibility; flexibility (as to lender structure and the mode of transacting) that compensates and corrects, rather than exploits, the borrowers’ lack of financial sophistication; and involvement of creditors or intermediaries representing debtors in activities that link borrowing for consumption to the generation and control of income and wealth for and by the community and its citizen-consumers.”

This is the sort of informality Abacus Federal Savings and other racial and ethnic minority banks pursue in furthering their mission of community development and reinvestment through home mortgage and small business loans.

There was nothing unusual about Abacus’s reliance on cultural expertise or informal mechanisms in underwriting and processing loans. A letter written to the bank by Fannie Mae, and read by the bank’s lawyer during his summation to the jury, recognizes the unique challenges posed by Abacus’s customer base of first generation Americans and thousands of small businesses. Although acknowledging that “doing anything customized in this environment is very difficult,” Fannie Mae committed itself to “doing whatever we can to develop solutions that meet the needs of your culturally unique clientele.”

It was the Manhattan D.A.’s exaggerated response to Abacus the Chinatown bank that was unusual. Unlike Fannie Mae, the Manhattan D.A. exercised no enlightened discretion in its pursuit of the bank in criminal court. Of course, the Manhattan D.A. may not have the most sophisticated understanding of the consequences that flow from excluding large numbers of productive people from formal credit markets, nor any idea of the sort of informality the democratization of formal credit requires.